By C.J. Bunce

Journalists in real-life tend to get a bad rap from folks who don’t understand how critical the Fourth Estate is in keeping the masses informed, upholding the First Amendment, and ensuring and fostering an open marketplace of ideas. Journalists in fiction have been portrayed as good or bad, reflecting the realities of any profession. Archetypes dating back from the days of yellow journalism survive to this day, in part because of the general nature of journalism and its origins as an apprentice-learned field. We emulate the past leaders of our professions to some extent. Journalists are practically unregulated. Regulations resulting from the 1934 U.S. Communications Act that protected the public and set boundaries for the profession have changed over the years, loosening restrictions on reporters (at least in the States) yet the news business draws the same personalities–driven people who get a thrill from searching for a needle in a haystack, who won’t give up until they can quote chapter and verse about that needle.

In mirroring reality over the years, Hollywood has shown us as time marches on what real journalists look like, what they do in their profession that we like and don’t like. You can see a shift from yellow journalism’s search for the biggest headline to journalists attempting to change the world, breaking barriers, asking questions, digging deeper, and often crossing the line to get the truth behind a story.

As Jeff Daniels, Sam Waterston and Jane Fonda headline The Newsroom, a new journalism-inspired TV series this airing this summer on HBO, let’s look at where Hollywood has done a good job (or not) in its depiction of newsrooms and their occupants.

I know a lot of journalism educators have their students watch some of these shows as part of understanding the history and nature of the craft of investigative reporting (mine did) and I often wonder just how much that has served to get students and future professionals in the mindset of the classic feet-on-the-street reporters. Case in point: It Happened One Night (1934) Clark Gable plays a reporter, cocky and sure-footed, yet a bit of a slacker who is not making the cut with his editor. He pursues a spoiled heiress who runs away from home, played by Claudette Colbert, to get a big headline for his paper, and becomes romantically involved with her by picture’s end. His reporter is the type depicted in film for the next several decades. Rodgers and Hammerstein’s 1945 film State Fair starred Dana Andrews as a reporter covering the Iowa State Fair for The Des Moines Register. Andrews’ confident character showed reporters as people to admire, and also illustrated that reporters are people, too, as he becomes involved with someone he meets (Jeanne Crain) while covering his story (like Gable’s character in It Happened One Night). Even Dustin Hoffman’s take on Carl Bernstein in 1976’s All the President’s Men seems to emulate this strident reporter attitude, adding a bit of renegade to the mix. Randy Quaid in the Ron Howard newspaper film The Paper is another variant on this guy–sleeping in the newsroom, seemingly some kind of drifter yet street smart, knows all the right people especially if part of the city’s underbelly, and just the guy you want when you need a partner on a big story. Although The Paper seemed more of a caricature of journalism–complete with Michael Keaton shouting “Stop the presses!”–it definitely is a lighter entry in the catalog of journalism films.

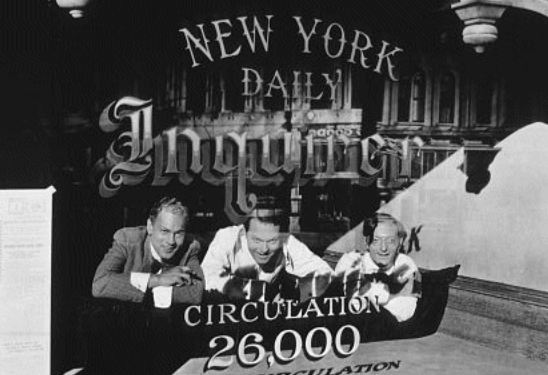

The newsroom is the center of the biggest film ever made, Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane (1939). Charles Foster Kane’s classic line: “I think it’d be fun to run a newspaper” connects with anyone running a journal, newspaper, or magazine. And as loud and off-the-wall as journalists are depicted here, Welles got the film absolutely right, basing the entire story on the life and times of media baron William Randolph Hearst. In pursuing the mysterious “Rosebud,” the journalist who bookends the story adds a double layer of truth with reporter as storyteller. The excesses of yellow journalism and the abuse of the medium permeated many mainstream movies of that era, including Frank Capra’s Meet John Doe (1941). Not entirely a newspaper movie, it does focus on an over-eager reporter played by Barbara Stanwyck who, like Kane, creates news where there is none for the sake of headlines.

Reporters as valuable, even crucial and noble members of society elevated the Fourth Estate to something of a venerable realm with movies like Call Northside 777 (1948). There Jimmy Stewart picks up a dead case of a man convicted of a crime that only his mother believes he didn’t commit. Based on a true story, Stewart’s reporter leaves no stone unturned in early Chicago, ultimately risking his own life to get the man out of jail (the film also reveals the first use of the lie detector machine as an investigative tool). The height of the importance of newspapermen, of course, came with the Washington Post bringing down a presidency, as documented perfectly in All the President’s Men (1976), a film whose newsroom could not better reflect a real-life, working newspaper office. Jason Robards, Jr. played Ben Bradlee as only a real editor could be played and Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman played young aspiring journalists Woodward and Bernstein in a mystery movie that could prompt anyone to enter the field.

The year 1976 also highlighted the more modern arm of journalism, broadcast journalism, in the popular film Network, which caused viewers to repeat forever the phrase “I’m mad as hell and I’m not going to take it anymore.” But here, it seems dated now, Faye Dunaway, William Holden, and Peter Finch just seem to have shed a light on the problems of any business in crisis, and despite its focus it does not make my recommendation list that well-document the journalist experience. However, where Network shone a dark light on broadcast journalism, the timely China Syndrome reflected the value of reporters in society. Jane Fonda’s bright and cheery fluff reporter who wants to report hard news is as real and inspiring as it gets, and Michael Douglas’s role as photographer who pushes the envelope to get a story rounds out a great reporting team.

Genre movies based on comic books have revealed to most of us our view of the editor and reporter in a big city newsroom, and the result doesn’t miss the mark so much. Jackie Cooper as The Daily Planet’s Perry White in Superman (1978) and later, Lane Smith’s work in the same role in the Lois & Clark (1993) TV series revealed a tough-as-nails editor every bit as real as Ben Bradlee at the real Washington Post, although Smith’s take brought Cooper’s 1950s-1970s era version into a version more familiar to 1990s newsrooms. A more cartoonish but similar role was played well by J.K Simmons as Peter Parker’s editor J. Jonah Jameson in Spider-man (2002).

Modern Hollywood, and perhaps modern audiences, latch onto the journalists as sleuths. That thrill and danger that may not be the stuff of daily working journalists certainly happens in real life from time to time and more modern films exemplify that. In Pelican Brief (1993) Denzel Washington gives a textbook performance as an investigative reporter. In The Insider (1999) Russell Crowe and Al Pacino reveal journalists as watchdogs, taking on big tobacco and the media themselves as politics prevents the long-time respected TV news show 60 Minutes from telling the story the reporters want to tell. Good Night and Good Luck took us back to the same CBS newsroom 40 years prior, as Edward R. Murrow (David Strathairn) and his team (including a memorable performance by Robert Downey, Jr.) take on McCarthyism in the 1950s. Veronica Guerin (2003) revealed the true story of a reporter played by Cate Blanchett whose pursuit of the story shows the extent reporters will go through for their cause–the pursuit of truth. There is simply no more exciting and gritty film about newspaper reporting than David Fincher’s Zodiac (2007), following Mark Ruffalo, Robert Downey, Jr. and Jake Gyllenhaal in pursuit of the Zodiac killer in 1970s San Francisco.

Most recently British television has reminded us that classic news stories still make compelling entertainment. You can probably ignore the U.S. remake of the same name starring Russell Crowe and Ben Affleck, but the British original TV series State of Play (2003) follows newshounds John Simm and Kelly MacDonald as they work for a brilliant newsroom manager played by genre actor Bill Nighy in their pursuit of the truth behind the death of a young political worker who may or may not have gotten too close to an up-and-coming politician. Like Robards, Cooper, and Smith mentioned above, Nighy crystallizes for us the role of the newsroom editor/manager. Then last year the BBC’s The Hour (2011) took us back to 1950s fledgeling broadcast journalism, including the pressures of England’s complex government and politics and the impact of censorship laws on the media. Romola Garai and Ben Whishaw star not as news anchors but producers behind the scenes in a refreshing new look at the business of news.

As media evolve into multimedia, Hollywood will no doubt keep pace with more fascinating storytelling, and we’ll be on the lookout for the next great journalism films.